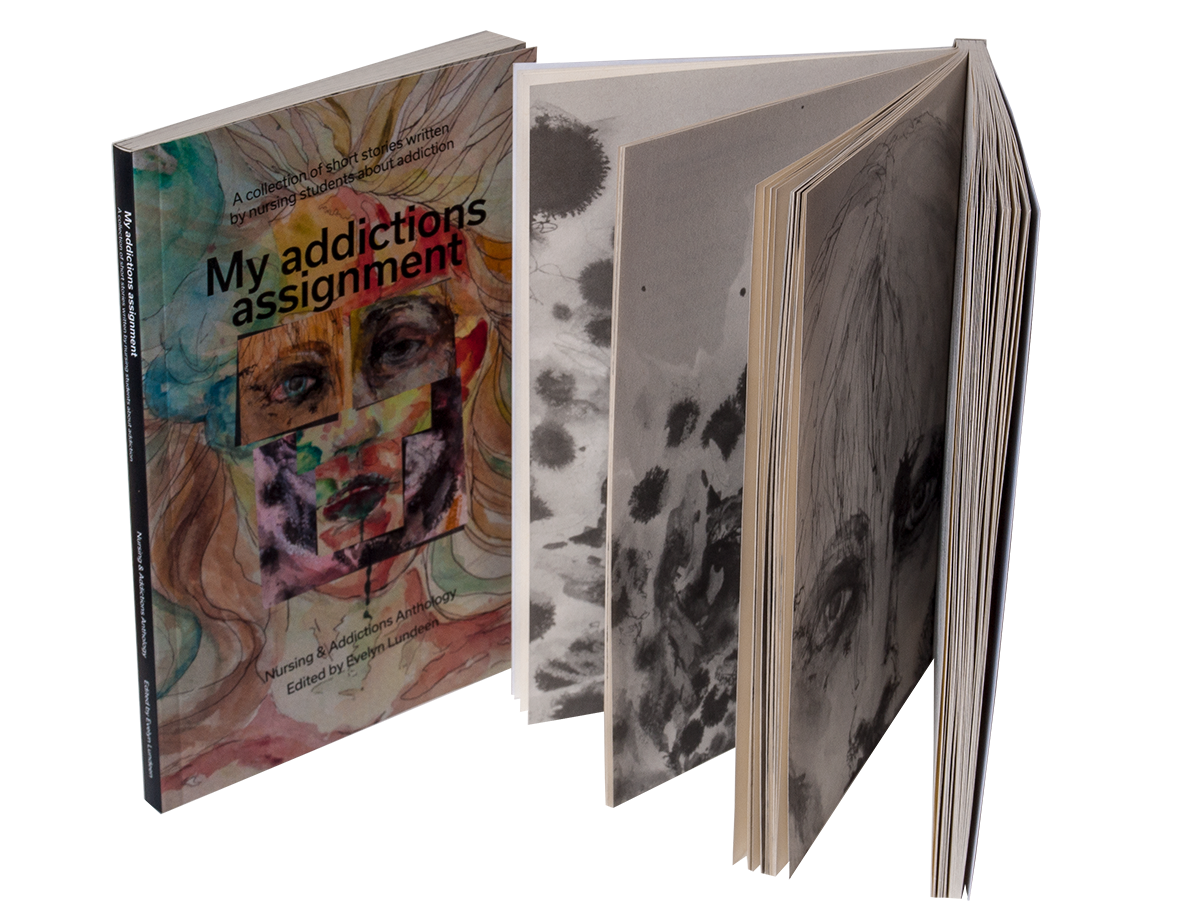

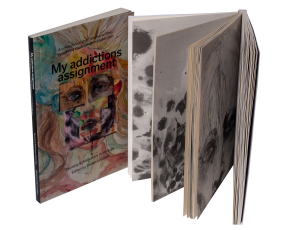

“My addictions assignment” is a collection of short stories written by nursing students at Red River College (RRC). MightyWrite has a connection to the project on a few levels. We did the layout and design of the book and our daughter, a student at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, did the striking illustrations. Finally, like many people, our family has its own stories of addiction – now more commonly referred to as substance use disorder.

In its #Get Loud campaign running during Mental Health Week, May 6 to 12, the Canadian Mental Health Association talks about how, with the right supports in place, we can be well, stay well and get out in front of illness.

With this in mind, I spoke to Evelyn Lundeen, RN, BN, MN, who is a nursing instructorat RRC’s School of Health Sciences and Community Services and editor of “My Addictions Assignment”. Having read Evelyn’s foreword for the book, I knew that raising awareness of the need for supportive interventions for people with substance use disorders was one of her intentions when she asked her nursing students to write about their experiences with addiction.

She wrote: Alcohol and drug addiction is a disease that affects the brain. It’s not a moral failing. It’s not a matter of “If you would just develop a backbone you could stop.” I’ve yet to meet an addict who wanted to be addicted. They all wish that beating addiction could be as easy as Nancy Reagan’s old slogan from the 1980’s – “just say no” to drugs and alcohol.

Addiction is a chronic debilitating disease like heart disease, diabetes, multiple sclerosis and a score of others. Do people with these disorders “just say no” and become healthy again? Of course they don’t. Do we tell an overweight individual who doesn’t exercise coming to hospital with a heart attack to go home, lose weight and start exercising; then come back to the hospital and we’ll help you? Of course, we don’t.

So why do we expect this from individuals with addiction? Why is an individual with alcoholism told to go home and sober up before help is offered? Why is an addict high on drugs sent home and told to come back when they are clear-headed?

On these last points Evelyn says, “If they could sober up themselves, they wouldn’t need to be in the ER in the first place.”

Not just another essay

During her decades-long career as a post-secondary instructor, Evelyn has reviewed many “cookie cutter” essays on a variety of topics. She didn’t want that from her nursing students. Rather, she wanted to help them discover the “art of caring,” which she says is another fundamental part of nursing. She hit upon the idea of having them write fiction that would release them from the confines of APA style and other guidelines whereby she’d often seen the ideas lost in all of the rules around academic papers.

What she saw instead, as the papers started coming in, was students telling stories about substance use disorders that drew on the course material to show what they’d learned. But she also saw something else.

“I noticed some were not fiction. These were narratives that some of these students had actually lived through,” she says. “They were writing about their father, mother, son, daughter, sister, brother, niece, nephew, grandma or grandpa.” In the foreword she wrote that these are the words that describe people living with addiction – not “Boozer,” “Wino,” or “Junkie.” Instead, she says, “It’s ordinary people like you and me.”

Because the quality of the stories was so good, she approached her Faculty Chair about turning them into a book. “The stories recognized that these peoples’ lives had value, that they were real people with hopes and dreams,” she says. She saw the book as an opportunity to create awareness and help dispel stigma around substance use. “People are so misinformed about substance use in general. I wanted to get across that this is a chronic illness and not a moral issue. It’s an illness that’s treatable like any other chronic illness.”

Shining a light on substance use disorder

Evelyn speaks from the heart as well as her experiences as both an instructor of the Addictions course in the Nursing program at RRC as well as an ICU nurse. “I want these new nurses to go out there with the right information,” she says adding that even doctors don’t always know what to do when people come in with alcohol or opiate problems.

When I asked her why this was so important to her she pointed to a photo on her desk of her best friend who died in 1999 of heart failure that was secondary to chronic alcoholism.  “He was just 45 when he died and was an RCMP officer whose career was ruined as a result of his drinking.” She says things might have been different for her friend today now that there’s better understanding and treatment available for officers. “Back then an alcoholic cop was not part of the RCMP image.”

“He was just 45 when he died and was an RCMP officer whose career was ruined as a result of his drinking.” She says things might have been different for her friend today now that there’s better understanding and treatment available for officers. “Back then an alcoholic cop was not part of the RCMP image.”

This is much the same for nurses. Evelyn recalls attending an in-service a few years ago when the conversation turned to nurses with substance use issues. “Some of what I was hearing was very troubling,” she says. “Supervisors talking with disgust about their colleagues or nurses working under them that had problems with substance use and how they felt they should be stripped of their licenses immediately and charged with an offence.” Evelyn says she understood their concerns about patient safety but says, “Taking their licenses away and throwing them in jail or fining them is not going to fix the underlying problem of substance use.”

When she was doing her Masters, she found a huge gap in anything related to addiction for nursing students. She made the case – and was successful – to have a course brought into the Nursing program at RRC. She first started teaching Understanding Drug and Alcohol Addiction – A Nursing Perspectiveabout five years ago. It was recently renamed Understanding Substance Use Disorders – A Nursing Perspective.

“We need to raise the profile of substance use disorder as a disease – it’s so relevant.” Under most human rights legislation, a substance use disorder is considered to be a disability. As Evelyn says, it affects both physical and psychological health.

An illness of the brain

“What people don’t understand is that substance use disorder is a disease of the brain,” says Evelyn. “It’s voluntary at the beginning but the changes that occur in the brain are permanent.”

She talks about how for thousands of years as a species, we humans have had to do certain things to survive. “This includes eating, consuming fluids, having sex, remaining safe and warm, getting adequate rest and sleep,” she says. In the case of substance users, this also includes consuming drugs or alcohol. She describes how our brains have an area called the reward pathway. “Whenever we indulge in an activity that gives us pleasure, the brain releases a burst of dopamine. This rush gives positive reinforcement, which means you’re going to want to do it again. With substance use disorder, the chemicals trick the brain into thinking they need it in order to survive.”

The prefrontal cortex is the area of the brain that allows you to perform executive function, which is all the activities you do on a daily basis that allow you to live in a very complex world. Evelyn shares that imaging studies show that individuals that are long-term substance users (decades) have less amount of tissue in that prefrontal cortex. This, she says, is particularly true if people start with substance use prior to the age of 25 when the brain fully matures. “If someone is doing substances before that, it doesn’t allow that part of the brain to fully develop. So, if you’re telling them to ‘pull up their socks’ they literally cannot do it, because they don’t have the brain function.” If they stop using they will eventually get some of that brain function back.

Finally, she talks about the area of the brain that is responsible for motivated behaviour, called the amygdala. While the description of what it does is much more complicated, involving a neurotransmitter called glutamate that is essential for transmitting messages between neurons that make thinking, learning and memory possible, Evelyn breaks it down this way. “The amygdala interacts with that reward pathway resulting in two behaviours – one is compulsion and the other is craving. There’s a voice in the back of the head that won’t shut up until you actually shut it up with the substance it’s craving.”

Approaches that support recovery and success – for everyone

The backbone of treatment for people with substance use disorder is psychotherapy and medication, which have proven to be successful in some populations. However, Evelyn shares, for many people, the sociological aspect also needs to be considered.

“When individuals go into a treatment program, they often do well – they have all the supports they need 24 hours a day for the duration of the program,” she says. “In addition to the psychotherapy and medication, their environment is safe and secure; they have access to clean water, a bed to sleep in, and healthy food to eat.”

When the program ends, Evelyn explains, these things sometimes go away. “The risk of a quick relapse escalates when they go back to live in the same circumstances that may have caused them to start using substances in the first place.” Issues like safe affordable housing, a living income, healthy food, access to education, money to pay for the medications they need to stay abstinent, and issues surrounding racism are things that cannot be dealt with in a rehabilitation program. “Unless those are addressed in an adequate fashion, the person who did so well in rehab is now set up to fail.”

In Evelyn’s opinion, more understanding is needed by the medical profession as well as society to better serve what she calls another “specialty area” of illness and treatment.

“We need to stop shaming people and recognize that this is an illness and that they need help to get well.” While she bristles at the idea that their use of drugs or alcohol is a choice, she agrees that individuals need to take personal responsibility to get well.

Evelyn also encourages family members to look into self-help resources like Al Anon, Al-Ateen or Adult Children of Alcoholics. Organizations like the Addictions Foundation of Manitoba (AFM) also have family programs that help affected members recognize family dynamics that occur when problematic substance use is present and how to deal with it.

“When you have someone with an addiction in the family, everything in the household revolves around that person. They may be getting the help they need but the core of the family has changed. If the family doesn’t get help as well they won’t be on the same page.”

Book, stories and illustrations well received

Evelyn says the response to the book has been very positive. “Everyone is commenting on the illustrations and how they fit well with the content. The use of colour and expressions; people found it very striking.”

The books are $20 each, and you can order copies by emailing elundeen@rrc.ca. Money raised will go toward a scholarship for a nursing student who is looking to specialize in substance use disorders.

The books are $20 each, and you can order copies by emailing elundeen@rrc.ca. Money raised will go toward a scholarship for a nursing student who is looking to specialize in substance use disorders.

Watch for an interview I’ll be sharing with Angela Fournier, the artist behind these illustrations.